I’ve been wanting to build an end-to-end ML project for a while now, and I finally had a fun idea: a cloud classifier! Here’s the GitHub repo. The end goal is simple: Build an app where you can take a photo of a cloud and get some standard classification of the cloud.

NOTE

Presented here is an retelling of some steps I took while working on this project. This post focuses on the first part of my project.

Table of contents

Open Table of contents

Can we do it?

How can we check whether the project is feasible? Well, there are some considerations.

-

Is there data available online?

The Cirrus Cumulus Stratus Nimbus (CCSN) dataset found in this paper looks good at a first glance. CCSN appears to be a pretty common ground photo dataset used in academic papers, and is also available on Kaggle. -

Has it been done before?

In academic papers, yes, but not too many times. One example is this research paper which compares different vision models on the CCSN dataset. Another example is this paper on self-supervised cloud classification from satellite images. I can only find a couple GitHub repos, with the top result being this one by Marcos Plaza on CCSN. Out of the handful of apps, almost all are paywalled and wrap a call to ChatGPT asking for a cloud type (what a shame). The best app I’ve found is the CloudSpotter app by the Cloud Appreciation Society (CAS). -

Are the compute/storage requirements reasonable?

CCSN is relatively small at 2543 jpg images, with each image averaging around 50kB in size. That’s perfectly reasonable to fit on my machine. Deep vision model training runs should take under a couple of hours, which is also reasonable.

This isn’t a bad place to start!

NOTE

If only I had known the enormous pain getting good data would be. It was never going to be as easy as finding something off Kaggle. But, that’s part of the fun after all.

Should we do it?

Well, a goal for the project is to create something original. Of the academic papers that use ground based photos, most use CCSN or data without cloud types like the SWIMCAT dataset. This encourages me as focusing on a deployable model is sufficiently original. There are some Kaggle notebooks for the CCSN dataset, but these feel far from a full project. Also, as I’ll cover later, CCSN isn’t so ideal for my own goal of making an app.

The only app that would deter me from building my own is CloudSpotter, but it has a couple of flaws:

- No uploading past images.

- No multi-label classification of clouds.

- No privacy of the images you upload.

- No web-based deployment.

The above gives me hope that I can nontrivially improve upon the lucrative cloud classification space. I also know that CloudSpotter pays people to label their data, as a friend told me their Geography PhD professor got offered the job! I can’t compete with access to paid labelers and a database of labeled user submissions, and that’s totally ok! CloudSpotter is a lovely app, and really does much more than just cloud type identification.

As far as I am aware, I can still work towards making an open source end-to-end cloud identification app using vision models and call it original.

The CCSN dataset

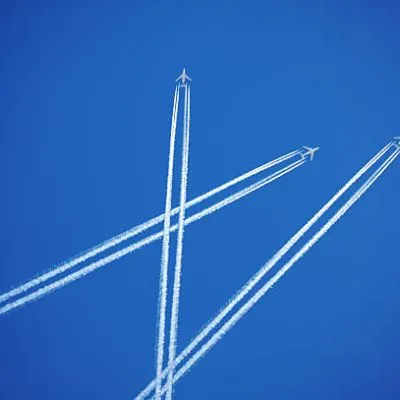

As stated above, the CCSN dataset from Harvard Dataverse is a common academic dataset with 2543 labeled cloud images. This labels include the 10 main cloud genera (cloud groups defined in the International Cloud Atlas) as well as contrails, a type of man-made cloud from airplanes. So CCSN provides a fine space of 11 cloud classes. Importantly, this data is single-label. Each image is tagged with one and only one of the 11 cloud classes available.

NOTE

The 10 main cloud genera are: altocumulus, altostratus, cirrocumulus, cirrostratus, cirrus, cumulonimbus, cumulus, nimbostratus, stratocumulus, stratus. Here’s a great place to learn more.

CCSN shortcomings

The CCSN dataset isn’t as good as you might think. The end goal is to deploy this classifier on an app, and so the distribution of cloud photos seen by the final model will be from cell phone cameras and amateur photographers. Additionally, the photos will probably be somewhat boring. This is an important point. The CCSN images look like they’re ripped straight from the Google Search for respective cloud types, and this means a lot of picturesque, sunset-time, and perfectly framed photos. My guess is that the distribution of cloud images in CCSN is fairly different from the distribution a model might encounter being deployed on an app.

Slightly cherry-picked sample of nine CCSN images. These don’t resemble the honest, hardworking clouds you see in the sky every day.

NOTE

The actual first dataset I found (SKIPP’D) had whole-sky fisheye lens images from an observatory. Super cool, but not ideal for this application!

Well, what can we do about this? We want a dataset that will most closely mimic the expected distribution of cloud images a deployed model will pull from. So, basically, we want mundane phone photos taken from the ground. Fortunately for us, citizen science comes to the rescue!

NASA GLOBE dataset

The NASA Global Learning and Observations to Benefit the Environment (GLOBE) program collects citizen scientist data from around the world and makes it freely accessible. Anyone can volunteer, download the app, and contribute.

Importantly, part of their data includes a sky conditions report where north, south, east, west, and upwards facing photos of the sky are taken. Users are then guided through a cloud identification wizard to report which of the 10 main cloud genera are visible in the sky. The real benefit of the NASA GLOBE dataset comes from the fact that the images appear to match the distribution of random cloud pictures you’d get on an app. Basically, they’re just more normal looking.

There also is an enormous amount of GLOBE data. In only about a year’s worth of GLOBE data I collected were 334,540 photos of the sky! There is also a great amount of guaranteed geographical & seasonal variety. The GLOBE data has labels for the main 10 cloud types, as well as for fog and contrails. There is loads of other information and metadata collected for each observation in the dataset as well.

Random examples of NASA GLOBE sky conditions images cropped to square shape. Hopefully the photos better match the distribution we’d expect from app photos. Can you spot the exceedingly rare cloud type above? It is indeed bona fide GLOBE data, and finding it absolutely made my day.

GLOBE shortcomings

Just like the CCSN dataset, the NASA GLOBE dataset also has some problems.

-

We only have access to cloud labels per observation.

Put differently, our 5 (North, East, South, West, Up) photos all share one set of labels. So a perfectly clear sky with one cumulus cloud in the North image will essentially label all images as having a cumulus cloud1. -

The labels are noisy.

The citizen scientists labeling the images have (understandably) made mistakes. While this is to be expected, and even CCSN has plenty of poor labels, these noisy labels are surprisingly prolific in the NASA GLOBE data. If the mistakes were just false negatives (the labeler missed a cirrus cloud, for example) it could be recoverable. But there is also an enormous amount of false positives. For example: labeling an image as the rare cumulonimbus cloud when in fact it is just a lame altocumulus. This really hurts our chances of making a good classifier. -

Some images aren’t clouds.

This is by far the least important problem, but it’s still worth mentioning. There are examples of near-black screens and photos of the ground submitted for all observation photos.

NOTE

At this point in the project I got very worried that no data would be good enough. In hindsight, CCSN probably would have worked. However, with the help of my friend Heather, I reached out Marilé Colón Robles, a NASA Langley scientist on the GLOBE team! She pointed me to NASA GLOBE CLOUD GAZE which I’d completely missed on the GLOBE website (oops). Thank you Heather and Marilé!

NASA CLOUD GAZE dataset

The NASA GLOBE CLOUD GAZE is a subset of the NASA GLOBE data born from a collaboration between NASA and the citizen science platform Zooniverse. How GAZE works is that NASA GLOBE photos are reviewed by multiple citizen scientists, only being officially classified and retired when:

- Consenus among labelers is reached. All labelers agree on on what types of clouds are in the photo.

- Enough classifications are taken. Eight labelers or 80% of those that classified the photo agreed on the result.

This ensemble of labelers gets us much much higher quality labels than the standard GLOBE data. Additionally, labelers can mark photos as having a blocked view, being blurry, or taken at night, and we can safely exclude these from our own training data. In total, GAZE gets us 13,500 well-labeled photos. While this is nowhere near as many as GLOBE, it is significantly more than the 2543 photos in CCSN.

NOTE

The GAZE data was actually only an 18-month prototype funded by the NASA Citizen Science for Earth Systems Program. Unforunately, the project wasn’t able to secure a full implementation, which would have granted an additional 3 years of funding. A real shame, imagine what could have been!

One last very important detail is that while GAZE selected observations from the GLOBE data, it has labels per-photo for each photo in the observation. That’s massive! GAZE solves all three problems from the regular GLOBE data. GAZE also has 5x as many photos as CCSN and the photos better match our assumption about the distribution of cloud photos in the wild. So the GAZE data is perfect, right?

GAZE shortcomings

The GAZE dataset, while amazing, is not perfect. The biggest issue is that the label space is different. Instead of the 10 cloud genera outlined by the International Cloud Association, the GAZE data has the following 7 labels for each photograph:

clearskycirrus or cirrostratuscirrocumulus or altocumulusaltostratus or stratusstratocumuluscumuluscumulonimbus

This is quite different from CCSN or GLOBE. Firstly, there is an explicit label for a clear sky. Additionally, cirrocumulus and altocumulus were combined into one label. This makes some sense as they are easy to confuse, both being a layer of small cloudlets (cirro clouds being the highest altitude while alto clouds are mid-range). The altostratus and stratus labels are also combined, and similarly they are both blankets of cloud primarily differentiated by height level. The combination of cirrus and cirrostratus is a little more confusing. They are both very high clouds and it’s possibly they are mislabeled frequently. What really confounds me is that there is no label for nimbostratus, the thick, gray, and somewhat depressing raincloud.

There are more labels available in GAZE such as contrails, smoke, and dust, but let’s ignore these as so few of the images actually have such labels. I know, I know. Contrail classification is hard to let go, as contrails are indeed clouds. However, to limit project scope, we’ll have to keep it all-natural for now.

This different labeling gives the GAZE data a unique tradeoff. We can’t classify as many cloud types but get enormous advantages in data quality. I think it’s a good idea to try and use the GAZE data for the time being. Primarily, the GAZE data gives us high quality data from a good distribution. Additionally, as far as I can tell, nobody else has tried training a classifier on the GAZE data! This is nice, as there are a couple of academic/Kaggle classifiers trained on CCSN.

Conclusion

Well, looks like GAZE is good enough for a first try. Tune in for another post in the near (?) future, when I feel the random urge to write again!

Footnotes

Footnotes

-

I am aware of multiple instance learning which bags together multiple instances (of cloud photos) with an observation level label. However, even with such methods I’m not convinced the raw NASA GLOBE dataset would work well. ↩